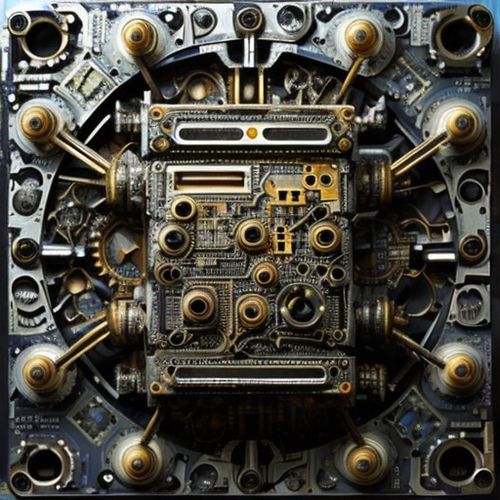

In recent years, a unique form of artistic expression has emerged from the shadows of electronic waste—collage art made from discarded circuit boards, capacitors, and other electronic components. While these intricate creations dazzle with their steampunk aesthetic and technological nostalgia, a darker reality lurks beneath their metallic sheen. Artists and environmental scientists alike are sounding the alarm about the heavy metal contamination embedded in these materials, raising urgent questions about workplace safety and ecological responsibility.

The process of dismantling old electronics for artistic purposes often releases toxic particulates into the air. Lead-based solder, cadmium in semiconductors, and mercury in switches—all these substances become airborne when artists grind, cut, or solder components for their mixed-media masterpieces. Veteran collage maker Daniel Mercer recalls developing persistent headaches after months of working with vintage computer parts. "I thought it was just creative exhaustion," he admits, "until my doctor asked about my studio ventilation system." Blood tests revealed elevated levels of three different heavy metals.

Workshops specializing in this art form frequently operate in converted industrial spaces with inadequate filtration systems. The very qualities that make e-waste visually compelling—the rainbow corrosion on copper traces, the powdery oxidation of aluminum heatsinks—are chemical warning signs that most self-taught artists misinterpret as harmless patina. Dr. Elena Vasquez, a materials scientist at MIT, has analyzed dust samples from twelve such studios. "Every single one showed concentrations of lead exceeding OSHA limits by 300-800%," she reports. "We're talking about exposure levels comparable to battery recycling plants in developing countries."

Beyond immediate health risks, the disposal of failed artworks creates secondary contamination pathways. Unlike functional electronics which fall under regulated recycling programs, art pieces occupy a legal gray area. When galleries discard unsold works or artists abandon experimental projects, these hybrid objects often end up in municipal landfills. Their elaborate combinations of plastics, metals, and adhesives make them virtually unrecyclable through conventional channels. The Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation recently traced elevated lead levels in a community garden to fragments of a decomposed e-waste sculpture illegally dumped five years prior.

Some artists have begun adapting their practice in response to these concerns. Barcelona-based collective "Circuito Cerrado" now exclusively works with components harvested under controlled conditions by certified e-waste facilities. Their pieces incorporate transparent resin encapsulation not just as an aesthetic choice, but as a containment strategy. "It's about finding beauty in tech's afterlife without unleashing its demons," explains member Lucia Herrera. They've developed a registry system documenting the origin and composition of every material used—an approach that's gaining traction among environmentally conscious collectors.

The art world's reckoning with this issue mirrors broader societal struggles around technology consumption. Each smartphone disassembled for its glittering guts represents both our thirst for innovation and our failure to manage its consequences. As museums begin acquiring these works for permanent collections, conservators face unprecedented challenges in preserving objects that might literally poison their storage facilities. The Whitney Museum's recent acquisition of a massive server-rack installation required special containment procedures typically reserved for radioactive medical equipment.

Regulatory bodies are starting to take notice. California's Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board is drafting guidelines specific to upcycling industries, while the European Union is considering extending RoHS restrictions to cover artistic reuse. These measures face pushback from grassroots creators who argue that bureaucracy will stifle an important cultural movement. "No one regulated the toxic pigments in Renaissance paintings," points out underground artist collective "Motherboard Mausoleum" in their manifesto. But health advocates counter that Caravaggio never worked with concentrated neurotoxins.

The dilemma underscores a painful truth about our relationship with technology: even attempts to romanticize its waste come with hidden costs. As the market for e-waste art grows—with pieces now commanding five-figure prices at major auctions—the sector stands at a crossroads. Will it evolve into a model of responsible material stewardship, or become another cautionary tale about good intentions colliding with physical realities? The answer may determine whether this avant-garde movement leaves behind cultural legacy or environmental liability.

Meanwhile, alternative approaches are emerging. "Bio-mining" artists collaborate with metallurgists to use fungi and bacteria that safely extract precious metals from components before artistic processing. Others focus on digital documentation rather than physical preservation, creating high-resolution scans of dangerous assemblies before their proper recycling. These innovators prove that creative adaptation—the very skill that birthed the movement—might also secure its future. As the glow of cathode-ray tubes fades from our collective memory, their material consequences demand solutions as sophisticated as the technologies they memorialize.

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 12, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 12, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 12, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025