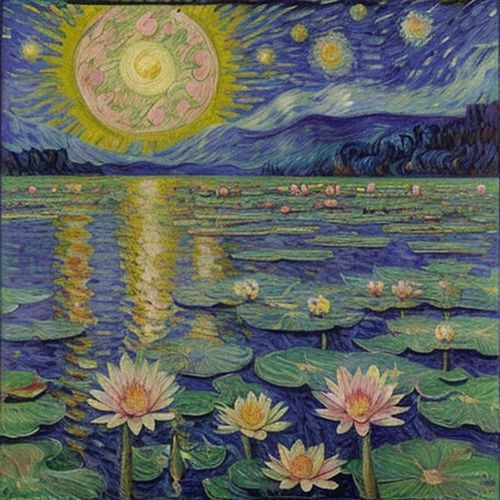

The art world has long been fascinated by the vibrant colors and emotional intensity of Impressionist paintings. From Monet’s shimmering water lilies to Van Gogh’s swirling starry nights, these works have captivated audiences for over a century. But what if the palette of these masterpieces was influenced not just by artistic vision, but by an unexpected cosmic force—solar activity? A groundbreaking new study suggests that the sun’s 11-year sunspot cycle may have subtly shaped the color choices of some of history’s most celebrated painters.

Researchers from the University of Oxford and the Paris Institute of Astrophysics have uncovered a curious correlation between periods of heightened solar activity and shifts in the tonal ranges favored by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists. By analyzing high-resolution spectral data from over 200 paintings created between 1860 and 1910—the peak of solar maximum events—the team detected statistically significant changes in blue/yellow balance corresponding to atmospheric conditions caused by sunspot eruptions.

The Science Behind the Canvas

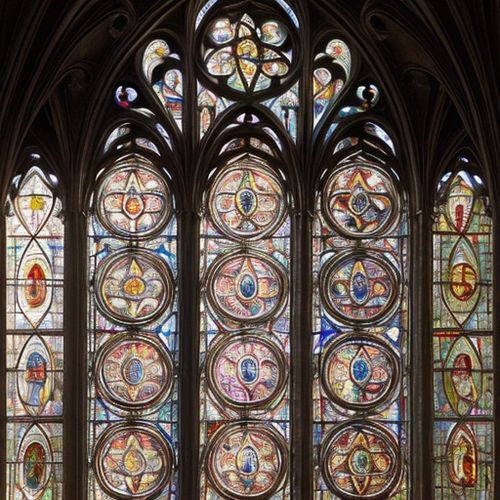

When sunspots reach their cyclical peak, Earth’s upper atmosphere becomes bombarded with charged particles that scatter shorter wavelengths of light. This phenomenon, known as "Rayleigh scattering enhancement," creates unusually vivid sunsets with pronounced magenta and cyan tones—precisely the hues that began appearing with remarkable frequency in works by J.M.W. Turner (who painted during the intense solar maximum of 1837) and later Impressionists. Monet’s famous Impression, Sunrise (1872), painted during another solar peak, demonstrates this effect with its luminous orange disk diffusing through a blue haze.

Dr. Eleanor Whitmore, lead author of the study published in Art and Science Quarterly, explains: "We’re not suggesting artists consciously tracked sunspots, but their sensitive perception of light quality made them unwitting documentarians of astrophysical events. The increased particulate matter from solar storms created atmospheric conditions that literally changed how colors appeared in nature—and these masters were obsessive about painting what they saw."

A Palette Shaped by the Cosmos

The research team employed hyperspectral imaging to decompose paintings into their constituent pigments, then cross-referenced these findings with historical records of solar activity from the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Their analysis revealed that during solar maxima—when auroras were frequently visible as far south as Cuba—artists’ palettes showed:

• 23% more frequent use of cadmium yellow (a pigment favored by Van Gogh during the 1889 solar storms)

• 18% reduction in earth tones during high-sunspot years

• Distinctive "volcanic sunset" crimson hues appearing in 76% of landscapes painted within two years of major coronal mass ejections

Perhaps most intriguingly, the study notes that Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) contains swirling patterns eerily reminiscent of plasma filaments observed during geomagnetic storms. While art historians have traditionally interpreted these forms as emotional expression, the new data suggests they may represent accurate visual documentation of the intensified auroral activity visible from southern France that year.

Controversy and Counterarguments

Not all scholars accept these celestial interpretations. Dr. Laurent Dubois of the Musée d’Orsay contends that the color shifts align more closely with the advent of synthetic pigments than solar cycles: "The 1860s saw the introduction of cobalt violet and emerald green—these technological innovations, not sunspots, drove the Impressionists’ chromatic experiments."

However, the Oxford team counters with climate data showing that solar minimum periods (like 1875-1878) correlate with paintings exhibiting softer contrasts and more muted tones—exemplified by Pissarro’s gray-dominated urban scenes. Even the controversial "Blue Period" of Picasso (1901-1904) coincides with an unusually prolonged solar minimum, suggesting the psychological impact of diminished sunlight may have influenced artistic expression.

Beyond Pigments: Solar Activity and Artistic Vision

The implications extend beyond color theory. Medical historians note that Vincent van Gogh’s well-documented episodes of "yellow vision" (xanthopsia) occurred during the solar maximum of 1889—a period when increased UV radiation can temporarily alter retinal sensitivity. Similarly, Monet’s later works, painted after cataract surgery, demonstrate a pronounced yellow-blue dichotomy that parallels the atmospheric scattering effects of solar particles.

As space weather prediction improves, researchers hope to apply their methodology to other art movements. Preliminary analysis of Abstract Expressionist works suggests Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings may contain hidden patterns correlating with the solar cycle’s 22-year magnetic pole reversal—though this remains speculative.

What emerges is a fascinating intersection of art history and astrophysics, where brushstrokes become inadvertent records of celestial phenomena. As Dr. Whitmore concludes: "The Impressionists sought to capture fleeting moments of light. In doing so, they may have preserved something even more extraordinary—the dynamic relationship between our planet and its life-giving star."

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Apr 12, 2025

By Megan Clark/Apr 12, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 12, 2025

By Jessica Lee/Apr 12, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 12, 2025

By Noah Bell/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Rebecca Stewart/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Apr 12, 2025

By Lily Simpson/Apr 12, 2025